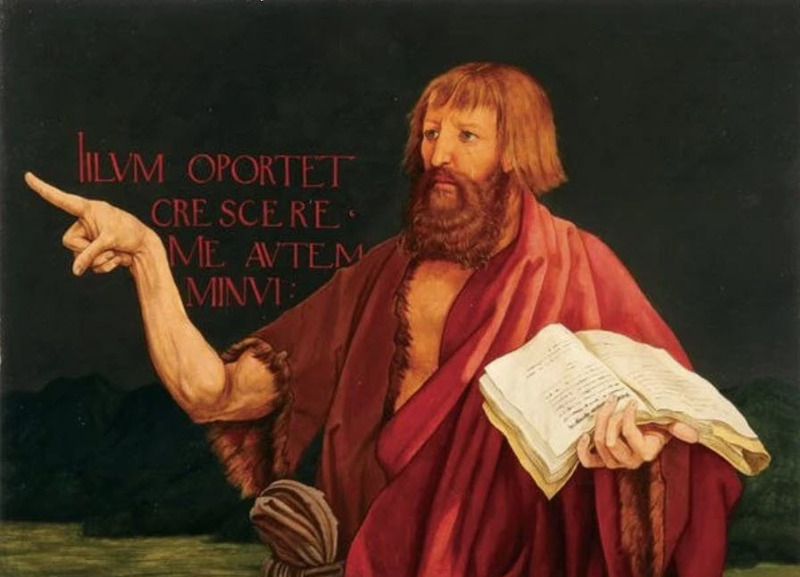

Image: John the Baptist from the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald.

We come to the Jordan River this week where we find John the Baptist yet again. But a much-diminished John. In this gospel, John doesn’t baptize anyone. He doesn’t even have the title of “the Baptist”. His movement is also significantly smaller. Where Matthew tells us that all Judea and Jerusalem were going out to see him, John tells us that only two of his disciples are with him on that second day at the Jordan. John is down to a church of three: himself, Andrew, and an unnamed disciple. Here, he stands as a witness, pointing his long, bony finger (as in the Matthias Grunewald painting) to Jesus, the Lamb who takes away the world’s sin.

But when he does so, he martyrs himself and his movement for the sake of Jesus and the gospel. Just as a tangent here: this is not a church growth strategy! It would be as if I said to you, “You know, I think you should all go to such-and-such Lutheran church and hear Pastor So-and-So. He is a much better preacher, better with children and youth, more consistent with his pastoral care, is always around when you need him, and by the way, tells better jokes!” The analogy isn’t perfect—after all, John is pointing to the very Messiah of God. But John is signaling the end of his movement, which should be the end of every preacher of the gospel: “Here is the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world.”

And what do his two disciples do after hearing this brief word? They go follow Jesus, of course! It’s no accident that the most effective sermons in Scripture tend to be the shortest. The prophet Jonah said, “Forty days more and Nineveh overthrown,” and Nineveh repented. Both John and Jesus preach elsewhere, “The Kingdom of God is near. Repent and believe in the good news.” And there is John’s sermon here. So, the disciples follow, but Jesus stops. He turns and asks them, “What are you looking for?”

We might consider the same question ourselves. When we consider Jesus, what are we looking for? John said, “This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world,” but what does that mean? Well, there are some things it doesn’t mean. There are three recurring expectations of Jesus which poison faith. The first is Jesus as fixer; the one who will solve all our problems and protect us from the consequences of our actions or inaction. Early in my ministry, I baptized someone who seemed to think of Jesus in exactly that way, no matter how much I tried to convince him that the Christian life is a marathon, not a sprint. That sort of expectation—that Jesus will just magic away all our problems—is a recurring one and has led to more idol-making than anything else. If Jesus won’t fix all our problems, we might try to find someone else who will.

This brings me to the second false expectation: Jesus as a bad cosmic therapist. In this expectation, Jesus is merely “someone to hear our prayers, someone who cares”. This Jesus doesn’t demand radical love and service. He doesn’t ask us to wash each other’s feet. He doesn’t exhort us to bear fruit or to abide in him. He merely accepts all our prejudices and messed-up worldviews as our own unique truth, no better or worse than anyone else’s. And most of all, that Jesus is here to soothe us, telling us, “It’s not your fault.”

The third is perhaps the most emblematic of our age. We might want Jesus to punish the people who really, really deserve it. Most, if not all of us have a long list of people in our heads who ought to get their just deserts. Vengeance or the threat of vengeance is everywhere, particularly in this age when mercy is perceived as weakness and self-giving love is for losers.

Jesus will meet none of these expectations. Rather, Jesus shows us a different way. Jesus lives out a new way of life, rooted in his Father’s love for a world gone its own way. And Jesus will give his life for the sake of that world; a world which includes all of us. Jesus will take away the world’s sin, which means far more than simply forgiving us of the things we do wrong.

Because we know that sin is far more than the things we do wrong. Sin, rather, is an addiction. We are born into a world that has fallen far from God’s intentions for it. We are wrapped up in a system bigger than ourselves seeking what is good, true, and beautiful, but in all the wrong ways. And we can’t help ourselves. We can’t. That doesn’t mean we aren’t responsible for our actions—we definitely are. But we are utterly powerless over this sinful system, which inducts us into its ways from our birth onward. That is where these false expectations for Jesus come from. That is where our false expectations for ourselves, our loved ones, our nation, and our world come from. We are ever and always “looking for love in all the wrong places”.

But Jesus comes to destroy that addiction to sin. That is indeed done in our baptism, but not in a magic kind of way. Rather, from the moment we are baptized, we become part of Jesus’s family—a family rooted likewise in God’s love for the world. Jesus takes away our sin through his love for us shown on the cross and sends us his Holy Spirit so that we may live a new life, as Paul writes. This is a struggle we have our whole lives long, I’m sorry to say. Baptism is a once and done thing, but the work of the Spirit continues. Luther wrote about this when he reminded us that “daily the old person in us is to drown and die through repentance for sin, and daily a new person is to rise up before God.” Sin isn’t magic-ed out. It is loved out. And this loving out of sin will continue until the day we die, which itself, as C.S. Lewis reminded us, is also part of the treatment. We have to die so that we can live.

But the comforting part in that is this: that very Lamb of God, who gave his life for us, still abides with us. John uses the Greek word translated “abide” or “remain” forty times in the gospel, and more still in the letters that bear his name. This Lamb will no longer die. He will not fade away. Whatever the world’s turmoil, whether in Roman Palestine in the 1st century or the United States in the 21st, Jesus our Lamb abides with us and we abide with him. This is what it means to bear fruit as a branch in his vine. That is what it means to do the works of God by believing in him whom God has sent. That is what the two disciples at the beginning of this gospel will begin to learn, and what we continue to learn our whole lives. The Lamb remains with us now and we will continue to be changed by him. Thanks be to God. Amen.

© 2026, David M. Fleener. Permission granted to copy and adapt original material herein for non-commercial purposes.